DMC ocean optics class builds an international community

In 1995, Emmanuel Boss took a class about Calibration & Validation for Ocean Color Remote Sensing. Three years later, he was a student teaching assistant.

Boss still keeps in touch with his instructors and fellow students in those classes. And the sense of community he felt taking the course inspired him to teach it, which he’s now done for 18 years.

This summer at the University of Maine Darling Marine Center in Walpole, he’s helping create a global network of oceanographers who focus on ocean optics — the study of light in the sea.

The network presents graduate students and early career scientists opportunities to collaborate, communicate and share important information and techniques that advance the field.

Light is essential to the ocean ecosystem because it drives photosynthesis, the foundation of the marine food chain and a major sink of carbon dioxide.

Scientists use optical sensors and remote satellites to study sunlight and how it interacts with material in the water.

These powerful tools monitor chemical and biological characteristics of the water on a worldwide scale. Ocean optics advances understanding of how oceans respond to pressures, including warming temperatures and acidification.

The course ran from 1985 to 2001 at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Laboratories, when UMaine professor Mary Jane Perry brought it to the University of Maine and the DMC.

“The DMC location, facility and scenery, together with a very demanding class are ideal for a group of strangers to become a caring cohort in a short time,” Boss says. “It’s a place to bond easily, a stress-free environment.”

Being detached from everyday life provides the perfect amount of isolation to focus on studies and connect with fellow classmates.

“It’s a great place for this class, for the combination of resources and the relaxing environment,” says Fernanda Maciel, a student at the University of the Republic in Uruguay.

Maciel is one of 20 students from 11 states and eight countries who gathered this summer at the DMC for the biennual four-week course.

Funded by NASA, the course has an international draw and is competitive. This year, one in five students were accepted, and formany it was their second or third attempt to get into the course.

The course content compliments many of the students’ research.

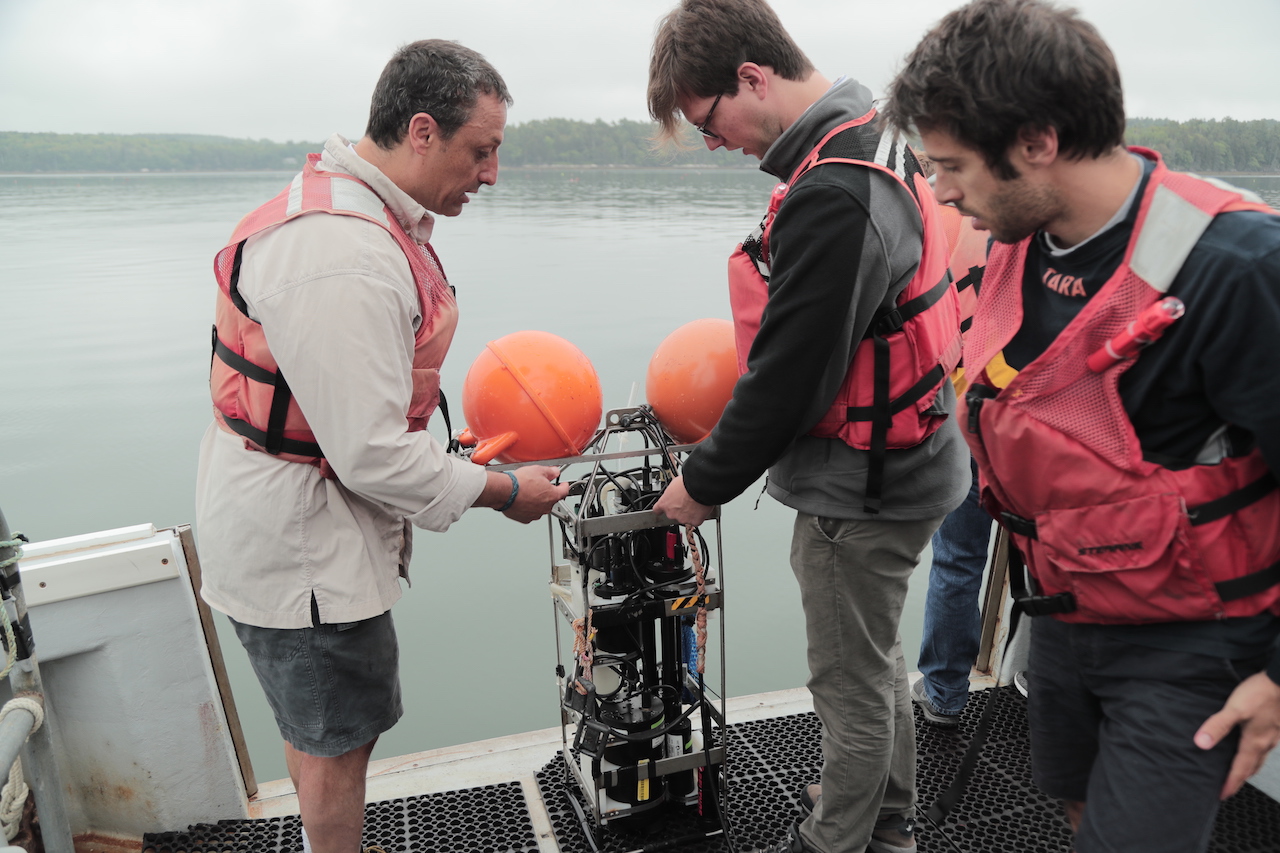

Harry Smith, master’s student at the University of Delaware, takes optical measurements with underwater robots. Smith was drawn to the class for its relevance to his project and the focus on remote sensing.

“I’m already using optics underwater,” Smith explains. “So it makes sense to study optics from space.”

For other students, the class was the perfect opportunity to get hands-on experience and gain skills.

“This class provided me with grounding principles and the chance to practice them,” Lydia Letaru, a recent graduate from Makerere University in Uganda, says.

She’s going to apply her knowledge of remote sensing to examine the water quality of Lake Victoria in Africa.

It wasn’t all work and no play.

Students lived in Brooke Hall on the lower waterfront campus, where they ate meals and spent much of their free time. In the evenings, students often studied and socialized in the common areas or played card games and Hacky Sack.

“Everyone here is going to do great things and now we will know each other for the future,” Letaru explains.

For Boss, this course changed his career path. It has provided him with a network of colleagues, which he now shares with these students.

The bonds these young professionals created this summer will be fundamental to their future endeavors. He looks forward to having some of them help teach the class one day.

“We’re making connections around the world,” Letaru reflects. “I’m grateful for the opportunity.”